Erdogan-Janus sera-t-il l’Antéchrist-2016?

Erdogan-Janus sera-t-il l’Antéchrist-2016?

Ex: http://www.dedefensa.org

Nous aurions pu choisir un titre plus long avec “Erdogan-Janus sera-t-il l’Antéchrist-2016 ou le Prophète-2016 ?”, mais l’on sait que nous n’aimons pas les titres trop longs, à dedefensa.org. Il fallut donc choisir entre les deux images, et ainsi notre choix indiquant le sens de notre commentaire : l’image de l’“Antéchrist” nous paraît mieux adaptée et bien plus féconde à ces temps d’abîme recélant les abysses insondables de la déstructuration-dissolution type-Fin des Temps. Donc, bonne année 2016.

En effet, cette rapide introduction permet également d’indiquer qu’avec Erdogan-2016 pris comme premier sujet de cette année nouvelle, nous ne nous attarderons certainement pas du tout aux thèmes usés et habituels du commentaire, que nous jugeons à la fois complètement dépassés, inappropriés, et complètement accessoires : qu’il s’agisse d’une part de l’analyse géopolitique classique, pleine de grandes manœuvres stratégiques, de Grands Jeux et de toute cette sorte de choses sérieuses des experts très-sérieux du domaine qui réfléchissent avec un sérieux qui vous tient en respect ; qu’il s’agisse d’autre part de l’analyse spéculative, bourdonnante de complots, d’explications cachées et mystérieuses, soudain mises à jour, que nous laissons aux spécialistes du genre, qui pullulent en tous sens et dans tous les sens avec un dynamisme et une constance, sinon une résilience, qui ne cessent de faire notre admiration. On sait que ces parfums de maîtrise de la raison humaine à tout prix, pour continuer inlassablement à nous expliquer le monde qui ne cesse de dérailler dans un tourbillon vertigineux, soit par des raisonnements sérieux et impératifs, soit par des supputations exotiques et enfiévrées, ne constituent en aucune façon nos tasses de thé habituelles. Nous aborderons le sujet par les aspects qui nous importent parce que nous les jugeons primordiaux, qui sont la psychologie et la communication, le symbolisme et le désordre, toutes ces choses où la maîtrise humaine n’a plus qu’un rôle de figurant effacé dont on pourrait aisément se passer sauf pour ce qui est de sa contribution au désordre.

Il est par contre une vérité-de-situation sur laquelle tout le monde doit s’entendre pour cette année 2016, c’est la place subitement très importante que le président turc Erdogan a pris sur la scène mondiale de l’immense désordre qui tient lieu aujourd’hui de ce qu’on nommait in illo tempore “les relations internationales”. (Et, disant “scène mondiale”, nous entendons par là qu’il ne faut pas cantonner Erdogan au seul théâtre moyen-oriental. Les effets de ses excès se font sentir sur tous les fronts, liant un peu plus la crise syrienne à d’autres crises, à la crise européenne avec la migration-réfugiés, à la situation crisique chronique aux USA avec la position de The Donald dans la course aux présidentielles, à la crise ukrainienne du fait du rapprochement antirusse d'Ankara vers Kiev, etc., et contribuant à renforcer notre conviction selon laquelle la vérité-de-situation générale caractérisant notre temps courant est bien que toutes les crises sont désormais fondues en un “tourbillon crisique” et constituent la crise haute, ou Crise Générale d’Effondrement du Système.) Plusieurs évènements ont contribué à cette promotion dont on ne sait si elle est, pour l’homme en question, un triomphe catastrophique ou une catastrophe triomphante. Rappelons-les succinctement.

• Depuis sa désignation comme président, cela accompagné de changements substantiels en préparation de cette fonction qui ferait désormais d’un président turc une sorte de monarque tout-puissant, de type “gaullien”, – pour la structuration institutionnelle sans aucun doute mais pour l’esprit c’est une autre affaire, – Erdogan a commencé aussitôt et par avance à exercer ce nouveau pouvoir vers une tendance de plus en plus autocratique, encore plus après les dernières élections qui ont donné une victoire incontestable à son parti. Le résultat intérieur a été d’abord cette extension accélérée de la dérive autocratique du régime tendant, avec une répression très fortement accrue contre toutes sortes d’opposition et de désaccord, allant jusqu’aux extrêmes de la violence pour réprimer tout ce qui peut être interprété comme du Lèse-Majesté, c’est-à-dire hors de la ligne autocratique. (A cet égard, nous sommes bien loin du gaullisme, article qui ne peut s’exporter que dans les vieux pays structurés par une tradition d’ordre et de mesure.) L’autre aspect intérieur a été une reprise sauvage et brutale de la lutte contre la minorité kurde liée évidemment au bouillonnement extérieur affectant d’autres minorités kurdes, en Syrie et en Irak. Cette attaque contre la minorité kurde prend, selon des sources kurdes et même humanitaires, des allures de nettoyage ethnique, voire des tendances à la liquidation qui fait naître des soupçons de tentation génocidaire.

• La personnalisation du pouvoir a mis en évidence la dimension mafieuse des tendances népotiques dont bénéficie la famille et le clan Erdogan. Cette dimension et ces tendances sont directement liées à un aspect jusqu’alors resté assez discret de l’activité d’Erdogan, mais qui se révèle aujourd’hui au grand jour : son soutien au terrorisme islamiste, où la Turquie supplante désormais les usual suspect, l’Arabie et certains Émirats du Golfe comme le Qatar. Les liens d’Erdogan surtout avec Daesh, ou État Islamique, sont spectaculaires : soutien logistique, soutien direct des forces spéciales et services spéciaux divers de la Turquie, soutien économique avec d’excellentes affaires dans le trafic désormais considérable vers la Turquie comme “point de vente” international du pétrole syrien et irakien que Daesh exploite sur les territoires qu’il contrôle. La famille Erdogan y montre toute l’habileté de ses tendances mafieuses en se trouvant au centre de cette organisation, avec les bénéfices qui vont avec.

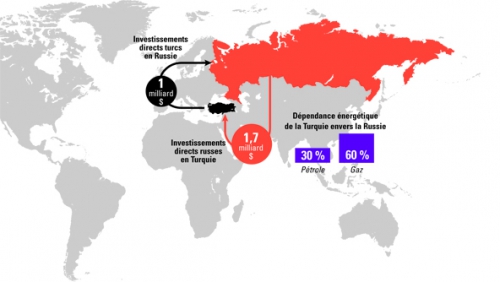

• La politique extérieure de la Turquie est désormais complètement bouleversée. Erdogan agit avec une brutalité sans nuances, que ce soit par rapport à la plupart de ses voisins (c’est l’inversion absolue de la formule de l’ancien ministre des affaires étrangères devenu Premier ministre Davutoglu, “Zéro problème avec nos voisins”), que ce soit dans les divers conflits où la Turquie s’invite désormais sans nécessité d’invitations, que ce soit enfin avec la Russie présente en Syrie depuis septembre 2015. Avec l’incident du Su-24 du 24 novembre 2015, les relations très-cordiales et tant bien que mal maintenues en l’état jusqu’à l’été 2015 entre Erdogan et Poutine, ont brusquement basculé. Depuis l’incident du 24 novembre, Erdogan n’a pas d’ennemi plus résolu et plus déterminé que Poutine, et il n’est pas assuré qu’il ait fait une excellente affaire à cet égard. Même un observateur aussi indulgent que MK Bhadrakumar, qui écartait au départ (après l’incident du 24 novembre) la possibilité d’une tension durable entre la Russie et la Turquie, juge au contraire que ces deux pays sont aujourd’hui “on a collision course”.

• Enfin, il y a les ambitions, sinon les rêves de puissance d’Erdogan. Cet aspect-là du personnage est désormais bien connu et tend à prendre une place démesurée dans son identification, dans une époque où la communication domine toute autre forme de puissance, et où le symbolisme joue un rôle fondamental, bien plus qu’une réalité objective dont on sait qu’elle n’existe plus, à notre estime. Les ambitions d’Erdogan, en forme de rêves ou de cauchemar concernent la restauration de l’empire ottoman, le rôle d’inspirateur et de quasi-Calife du monde musulman. Pour certains, il est un Prophète, sinon un Dieu ; pour d’autres, il n’est rien de moins que l’Antéchrist. Un personnage d’époque, dans aucun doute.

... A côté de tout cela, il y a une réelle évolution, encore souterraine mais grandissante, du sentiment général du bloc-BAO vis-vis de la Turquie, à cause des frasques provocatrices d’Erdogan (surtout vis-à-vis de la Russie) autant que du rôle plus que douteux qu’il a joué dans la vague de migration des réfugiés syriens vers l’Europe depuis l’été 2015 d’une façon ouverte. Désormais, des commentateurs de médias d’influence dans le Système, comme le site Politico à Washington (le 30 décembre 2015), s’interrogent sur la capacité de nuisance d’Erdogan, c’est-à-dire la possibilité que ses interférences puissent provoquer l’enchaînement vers un conflit de grande importance. Il s’agit de l’hypothèse désormais souvent évoqué qu’Erdogan, provoquant une tension débouchant sur un confit avec la Russie, n’entraîne l’OTAN dans un conflit avec la Russie au nom du fameux Article 5 (dont on oublie en général qu’il n’a pas d’aspect formellement contraignant sur l’essentiel, puisqu’est laissé à l’estime des États-membres le choix de l’aide à apporter à celui qui la réclame, cette aide pouvant par exemple consister simplement dans l’envoi d’un soutien médical). C’est ainsi, au niveau du système de la communication et par la grande porte de l’hypothèse potentiellement nucléaire qui n’a jusqu’ici été évoquée dans la séquence actuelle qu’avec la crise ukrainienne, et seulement à cause de l’implication directe de l’OTAN et des USA, que la Turquie s’est installée au centre du désordre général et international. Il ne s’agit pas de savoir si un conflit nucléaire est concevable ou pas, il s’agit de voir que la Turquie est désormais l’élément central donnant aux commentateurs la possibilité d’évoquer l’hypothèse. Sans doute est-ce ce qu’on appelle, dans notre langage-Système affectionné des salons, “jouer dans la cour des grands”, – c’est-à-dire manier les risques et les sottises pour des hypothèses de première catégorie...

« 2015 is drawing to an end. The unanswered questions of the year — especially the ones related to ISIL, Syria and the massive flow of refugees from the region into Europe — are being carried over onto 2016’s balance sheet. So are the unasked questions. Chief among them is, “For how long will you tolerate the government of Turkey, a member of NATO and would-be member of the EU, taking steps that make defeating ISIL, or Daesh, more difficult?” And, as a supplementary question to the leaders of Europe, “Why are you buying off the government of Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan to gain its cooperation in dealing with all the problems arising from the disintegration of Syria? Shouldn’t his cooperation be part and parcel of membership in a democratic ‘alliance’?”

» But that is small beer compared to a month ago, when a Turkish fighter jet shot down a Russian plane. Since then tensions have grown between the two countries. The Turkish newspaper Zaman reports of renewed tensions between the two countries in the south Caucasus, saying that defense officials in Ankara claim “it is only a matter of time before the tension over Nagorno-Karabakh relapses into war.” If there is another incident — and given how crowded the skies along the Syria-Turkey border are, it can’t be ruled out — and Russia decides to retaliate by shooting down a Turkish jet, what happens then? Turkey is a NATO member and would be within its rights to invoke the Article 5 “collective defense” response.Would the Alliance really go to war against Russia then? »

Il y a aussi, comme nous l’avons évoqué, la dimension mystique et mythique dont commence à être habillé Erdogan, avec ses rêves de grandeur et ses conceptions teintées de références coraniques, bibliques, etc. Comme nous l’avons suggéré plus haut, les images de “Prophète” voire de “dieu”, de “Calife” d’un empire reconstitué, etc., ne nous intéressent guère parce qu’elles renvoient trop au théâtre intérieur et régional autour d’Erdogan, même si le but ultime de l’une ou l’autre de ses fonctions est bien évidemment, comme allant-de-soi, la conquête du monde. L’image d’“Antéchrist” est plus intéressante, parce que, dans les circonstances actuelles, utilisable comme référence religieuse qui, dans l’appréciation générale, est perçue comme catastrophique dans une époque qui ne l’est pas moins (catastrophique). Bien entendu, il ne s’agit pas de s’attacher à la référence religieuse en tant que telle, qui nous promet le retour du Christ après l’Antéchrist (ou “AntiChrist”, débat toujours en cours), car ce serait entrer dans le labyrinthe sans fin ni issue de la théologie. Il s’agit de prendre acte d’un fait du système de la communication qui s’est développé autour d’Erdogan et qui prend d’autant plus d’ampleur avec la politique de la Turquie, son activisme, son imbrication avec les courants activistes religieux, etc., au cœur du “tourbillon crisique”.

Un exemple de l’argument d’Erdogan-Antéchrist est donné par une longue analyse sur Shoebat.com par Walid Shoebat. Il s’agit d’un personnage contesté et qui se justifie longuement sur son site, mais le but n'est ici que de lire l’analyse du développement du culte d’Erdogan et des références à partir des Écritures Saintes pour justifier et créditer cette perception en plein développement d’Erdogan. L’intérêt de ce texte du 27 décembre 2015 est évidemment qu’il rencontre effectivement une communication de plus en plus insistante autour d’un personnage (Erdogan) de plus en plus défini par son caractère d’impulsivité et d’hybris mêlé de références religieuses qu’il favorise lui-même. Nous en donnons ci-après quelques extraits qui donneront une impression assez précise du travail accompli, – en d’autres termes, de l’importance que certains accordent, avec références à l’appui, à la dimension disons eschatologique qu’Erdogan est en train d’accorder, ou de laisser accorder à ses propres mesures. (Le titre de ce texte est : “Erdogan vient d’être proclamé le chef du monde musulman, et les musulmans l’appelle d’ores et déjà ‘Dieu’”)

« As he wrote for Yeni Safak, the pro-Erdogan main newspaper under the control of Erdogan in Istanbul. In his article regarding the new presidential system which Erdogan wants to establish, Karaman desperately defended Erdogan and declared what we were saying all along they will do; that Erdogan will soon become the Caliph for all Muslims. The following is a presentation of the exciting part in an article Hayrettin Karaman wrote: “During the debate on the presidential system, here is what everyone must do so while taking into account the direction of the world’s national interest and the future of the country and not focus on the party or a particular person. What this [presidential system] looks like is the Islamic caliphate system in terms of its mechanism. In this system the people choose the leader, the Prince, and then all will pledge the Bay’ah [allegiance] and then the chosen president appoints the high government bureaucracy and he cannot interfere in the judiciary where the Committee will audit legislation independent of the president. ”

» This one statement yields a multitude of prophetic consequences. Bay’at, as Islam calls it, which is “giving allegiance,” is the hallmark of the Antichrist as John declared: “but the fatal wound was healed! The whole world marveled at this miracle and gave allegiance to the beast” (Revelation 13:3). And here this man who is given allegiance to is called “The Prince”, exactly as predicted in Daniel 9:26. Erdogan qualifies to be “king of fierce countenance” (Daniel 8:23)

» Karaman is the major Islamist fatwa-giver in Turkey, one of Erdogan’s main henchmen and a practitioner of Muruna, the Muslim Brotherhood’s allowance for sanctioning Islamic prohibition in the case of Jihad, which means that the Mufti can bend Islamic Sharia to produce favorable fatwas, whatever it takes to establish an Islamic Caliphate. Hosea 12:7 tells us of the Antichrist: “He is a merchant, the balances of deceit are in his hand: he loveth to oppress.” The “Balance of deceit” is exactly how the three decade Islamic doctrine, Muruna, is defined as the “Doctrine of Balance” where a Muslim can balance between good and evil and is sanctioned to do evil for the sake of victory. “He will be a master of deception and will become arrogant; he will destroy many without warning.” (Daniel 8:25) [...]

» When Erdogan’s party had a major setback, many thought it was his end. But by meticulous study of Daniel’s text, we accurately predicted the reverse will happen (and we were accurate to the letter): For the first time in 13 years, the Turkish AKP, led by President Erdogan and Prime Minister Davutoglu, has lost its majority hold on the parliament which held 312 of the 550 seats in parliament and now only holds 258 seats while the other three (CHP, MHP and HDP) now has 292 seats. So does this set back mean the end for Erdogan and the AKP Party and are we to now eliminate the man of Turkey as the wrong candidate from being the Antichrist?

» Hardly.

» In fact, such a loss bolsters the biblical argument since unlike what most imagine, that the Antichrist storms in because through his charisma he gains a popular vote. On the contrary, Antichrist, as we are told by Daniel, does not gain prominence by majority support: “With the force of a flood they shall be swept away from before him and be broken, and also the prince of the covenant. And after the league is made with him he shall act deceitfully, for he shall come up and become strong with a small number of people.” (Daniel 11:23)

» The Antichrist, when he emerges, he forms a league and advances with a small number of supporters. Historically, the AKP began from a small number of people, the Refah Welfare Party which participated in the 1991 elections in a triple alliance with the Nationalist Movement Party (MHP) and the Reformist Democracy Party (IDP) to gain 16.9% of the vote. It was truly the incumbent PresidentRecep Tayyip Erdoğan, a former member of the party, but later founded Justice and Development Party (AKP) who catapulted the AKP to what it is today which still holds over 40 percent of the seats defeating all the other three. This is truly a victory for the Erdogan who started with “a few number of people”. »

L’homme de l’avant-dernier Jugement Dernier

Dans ces diverses constatations, observations et citations, il y a beaucoup de choses , ou comme l’on dit “du grain à moudre”, – beaucoup trop, en fait. Il importe de faire la part des choses et, puisque nous sommes dans le lieu commun, de “séparer le bon grain de l’ivraie”. Ce qui nous importe, c’est la rencontre de circonstances diverses, chacune avec un grand effet de perception quelles que soient leur importance et leur véracité. Il est certain qu’Erdogan avec son habillage en Antéchrist devient un personnage symbolique de grande importance, qui s’inscrit parfaitement dans son époque pour y représenter la part la plus spectaculaire au sens d’une “époque de spectacle” (comme la fameuse “société du spectacle”), la plus génératrice de désordre, mais aussi la plus symbolique des fondations eschatologiques de notre Grande Crise.

Ce dernier cas est caractéristique de l’interprétation qu’il nous importe de donner : figurant comme une narrative, même si certains sont tentés de prendre la chose au sérieux pour se prosterner devant elle ou pour la dénoncer, indiquant que notre Grande Crise cherche par tous les moyens à se définir elle-même comme eschatologique, comme fondamentale, comme embrassant le domaine de la spiritualité. C’est une sorte de “point Oméga” (inverti) où la narrative peut conduire, sans le vouloir précisément parce qu’ignorant complètement cette notion de “vérité”, à une vérité-de-situation fondamentale...

Certains verraient alors une complète logique dans l’affrontement d’Erdogan avec Poutine, dans la mesure où le président russe est de plus en plus perçu comme défenseur de la Tradition, ou plus précisément comme défenseur du christianisme... Mais alors nous considérerions qu’il s’agit là d’une symbolique religieuse où le christianisme que défend Poutine et tel que le défend Poutine, quoi qu’il en pense et en dise, n’est effectivement qu’une représentation symbolique de la Tradition contre la déstructuration-dissolution de la postmodernité dont Erdogan-Antéchrist pourrait aisément, quoi qu’il en pense et dise lui aussi, devenir la représentation symbolique, s’avançant masqué de sa mine de “Calife à la place de tous les califes”. Les incroyables nœuds d’accointances, d’alliances et de désalliances qui caractérisent la crise dite Syrie-II, où Erdogan évolue comme un poisson dans la nasse, le labyrinthe kafkaïen de certaines politiques que personne ne parvient plus à identifier, – particulièrement l’antipolitique américaniste, plus que jamais “histoire pleine de bruit et de fureur, racontée par un BHO et qui ne signifie rien”, – pourraient aisément justifier cette position du Calife-Antéchrist, voire quasiment la légitimer selon la sorte des principes absolument invertis dont se goinfre la postmodernité. Dans cet univers et cette situation, tout est effectivement possible, et particulièrement le factice, l’apparence, la construction déconstruite, les palais au mille-et-unie pièces privé de poutres-maîtresses et ainsi de suite ... Il est effectivement temps qu'arrive un Antéchrist, et qu'on en soit quitte : alors, pourquoi pas Erdogan-Antéchrist puisqu’il devrait être logique de penser qu’on a l’Antéchrist qu’on peut ?

Cela permettrait d’autant mieux apprécier la solidité et la durabilité de cette prétention symbolique ainsi réduite à un désordre indescriptible qui conduit le Calife-Antéchrist, en même temps qu’il proclame son intention de soumettre le monde entier, à mettre le feu dans sa propre maison, que ce soit dans les flammes d’un régime d’exception qui ne fait que refléter une paranoïa perdu dans les mille-et-une pièce du palais présidentiel (1006 exactement, selon certaines sources indignes de foi), que ce soit dans une fureur prédatrice exercée contre les Kurdes. Il ne faut pas voir dans l’ironie qui sourd dans ces diverses observations la moindre volonté de réduire à rien la nouvelle position d’Erdogan, ses ambitions, etc., mais simplement un souci d’illustrer une époque comme un Tout absolument constitué en simulacre, – ce qui implique l’obscure mais mortelle faiblesse du Système qui s’est voulu l’architecte de la chose et ne cesse de chercher à détruire tout ce qui est architecture.

Sans le moindre doute et si l’on se place dans la perspective du véritable tragique qu’est l’histoire du monde, que sont nos grands mythes, les origines de nos grandes pensées et de notre spiritualité, le constat se trouve absolument justifié qu’Erdogan est faussaire en prétendant être l’Antéchrist, ou en laissant dire dans ce sens, qu’il ne fait que céder à un goût de la représentation que lui impose son hybris. Mais n’est-ce pas la fonction, voire la substance même même de l’Antéchrist qu’être faussaire, après tout, et précisément dans cette époque constituée d’inversion et de subversion, d’imposture régulièrement et presque heureusement assumées à ciel ouvert comme s’il s’agissait de la recette même du bonheur ? Dans ce cas, Erdogan n’est pas déplacé dans ce rôle, et sa survenue dans ce sens répond à une logique supérieure qui, elle, répond au tragique de l’histoire du monde. Il s’est transformé en cette représentation symbolique à mesure que la Grande Crise, devenue “tourbillon crisique” acquérait des dimensions eschatologiques, et parce qu’elle acquérait ces dimensions (la Grande Crise-devenue-eschatologique enfantant Erdogan-Antéchrist et non l’inverse). En ce sens, il serait devenu ou deviendrait Antéchrist pour accélérer la transformation surpuissance-autodestruction et alors cette imposture, cette magouille doivent lui être pardonnées parce qu’il est alors Antéchrist et Janus à la fois, et pour l’instant la meilleure chance pour 2016 d’accélérer l’effondrement du Système.

Erdogan, que nous jugions vertueux il y a quelques années, et malgré tout avec de justes raisons de porter ce jugement, transformé en ce qu’il est devenu à mesure que la Grande Crise se transformait elle-même et lui imposait cette voie, voilà ce que nous réserve 2016 en une nouvelle tentative de cette Grande Crise de trouver la voie vers le paroxysme d’elle-même. Simplement, et là nous séparant de la religion, nous croirions aisément que cette transformation est de pure communication, faite pour exciter des perceptions et susciter des réactions, également de communication, toujours à la recherche de l’enchaînement fatal vers l’autodestruction. Cela signifie que la Troisième Guerre mondiale n’est pas nécessairement au rendez-vous et sans doute loin de là avec leur sens du tragique réduit à la tragédie-bouffe, mais cela n’enlève rien à l’importance de la chose ; l’on sait bien, aujourd’hui, que toute la puissance du monde est d’abord rassemblée dans le système de la communication, que c’est sur ce terrain que se livre la bataille, qu’il s’agisse de la frontière turco-syrienne ou d’Armageddon.

Si cette interprétation symbolique est juste comme nous le pensons avec toutes les réserves dites dont aucune n’est en rien décisive, alors Erdogan est destiné à tenir un rôle important de provocateur, et très vite puisque tout va si vite aujourd’hui, pour attiser les feux de la crise parce que la dimension eschatologique l’exige. Nous prêterons donc attention à l’écho de ses terribles colères dans les mille-et-une pièces de son palais dont la prétention et le massivité de l’architecture (voir les photos présentées par l’article du Wikipédia, déjà référencé) nous font penser, pour l’esprit de la chose, à l’immense construction de son propre palais à laquelle avait présidé Ceausescu, à Bucarest, dans le bon vieux temps de la Guerre froide d’avant la chute du Mur. La construction et la constitution de cet événement architectural, et les péripéties qui l’ont accompagné, y compris l’ardoise au complet (€491 millions), font partie de ces “petits (!) détails” dont raffolait Stendhal, parce qu’ils disent tout de certaines grandes choses dont on tente de percer les mystères par la puissance de la seule raison : une telle construction pourrait constituer une preuve irréfutable de la constitution du président Erdogan, l’esprit emporté par la Crise, en Calife-Antéchrist dont on attend beaucoup en 2016 dans le rôle de l’allumeur de mèches nécessaire pour conduire à de nouveaux paroxysmes.

Pour terminer, on notera avec respect l’exceptionnelle position de stupidité contradictoire et d’aveuglement satisfait de l’Europe qui, pendant ce temps et malgré le doute de certains à l’encontre d’Erdogan, s’affaire à préparer la voie vers l’intégration de la Turquie en son sein pendant que son extraordinaire couardise sécuritaire parvient à handicaper encore plus son économie dans les remous d’attentats prétendument préparés par des organisations subventionnées au vu et au su de tous par la susdite Turquie, attentats déjoués par paralysie de l’activité. La perspective d’un processus, qu’on voudrait sans doute accéléré, d’intégration de la Turquie dans l’Europe constituerait une voie qui ne manquerait pas d'élégance pour achever l’effondrement de cette construction étrange qu’est l’UE, elle aussi comme un émanation, conceptuelle cette fois, des palais combinés de Erdogan-Ceausescu. Nous ne sommes pas loin de penser que la Grande Crise d’Effondrement du Système (CCES en abrégé) est d’abord et avant tout la plus grande tragédie-bouffe de l’histoire du monde : notre contre-civilisation, toutes réflexions faites, ne peut vraiment s’effondrer que dans le ridicule d’elle-même. Cela n’atténuera pas les souffrances ni les angoisses de ceux qui en sont affectées, mais il faut savoir distinguer où se trouve l’essentiel : le ridicule serait finalement l’arme absolue de l’esprit antiSystème, c’est-à-dire la chimie ultime transformant la surpuissance en autodestruction, que nous ne serions pas plus étonnés que cela...

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

According to the Turkish parliament’s official press release regarding the natural gas agreement between BOTAS and Qatar Petroleum, Erdogan said, “As you know, Qatar Petroleum has had a bid to invest in LNG in Turkey for a long time. Due to the known developments in Turkey, they are studying what kind of steps they could take in LNG and LNG storage. We expressed that we viewed their study positively. As you know, both the private and public sector have LNG storage facilities. This one will be an investment between governments.”

According to the Turkish parliament’s official press release regarding the natural gas agreement between BOTAS and Qatar Petroleum, Erdogan said, “As you know, Qatar Petroleum has had a bid to invest in LNG in Turkey for a long time. Due to the known developments in Turkey, they are studying what kind of steps they could take in LNG and LNG storage. We expressed that we viewed their study positively. As you know, both the private and public sector have LNG storage facilities. This one will be an investment between governments.”

Erdogan était jusqu'ici apparu aux yeux de nombreux observateurs comme un personnage vaniteux et autoritaire, tenté par le rêve de réincarner à lui seul l'antique Empire Ottoman, un personnage finalement maladroit.

Erdogan était jusqu'ici apparu aux yeux de nombreux observateurs comme un personnage vaniteux et autoritaire, tenté par le rêve de réincarner à lui seul l'antique Empire Ottoman, un personnage finalement maladroit.

Pour poursuivre son rêve de puissance, le Président turc a doublement utilisé la peur, celle que son armée peut susciter par ses interventions contre les rebelles kurdes et celle que le peuple turc ressent à mesure que la violence se répand sur son territoire. Le 10 Octobre, une manifestation kurde est touchée par un attentat sanglant qui fait 102 morts. L’Etat islamique est accusé. Pour laver l’affront, l’aviation turque va mener des opérations punitives, mais elle bombarde surtout les Kurdes, doublement victimes. L’AKP se fait le gardien de la sécurité et rassure en se dressant à la fois contre Daesh et le PKK. Une partie des nationalistes du MHP reporte ses voix sur elle. Les pressions sur les médias, la monopolisation de l’information, des irrégularités relevées par l’OSCE font le reste. L’AKP a retrouvé la majorité absolue. Erdogan peut de plus belle entretenir la rébellion syrienne, lâcher des milliers de migrants chaque jour sur l’Europe et obtenir de la décevante Mme Merkel des signes favorables à l’adhésion de la Turquie à l’Union Européenne.

Pour poursuivre son rêve de puissance, le Président turc a doublement utilisé la peur, celle que son armée peut susciter par ses interventions contre les rebelles kurdes et celle que le peuple turc ressent à mesure que la violence se répand sur son territoire. Le 10 Octobre, une manifestation kurde est touchée par un attentat sanglant qui fait 102 morts. L’Etat islamique est accusé. Pour laver l’affront, l’aviation turque va mener des opérations punitives, mais elle bombarde surtout les Kurdes, doublement victimes. L’AKP se fait le gardien de la sécurité et rassure en se dressant à la fois contre Daesh et le PKK. Une partie des nationalistes du MHP reporte ses voix sur elle. Les pressions sur les médias, la monopolisation de l’information, des irrégularités relevées par l’OSCE font le reste. L’AKP a retrouvé la majorité absolue. Erdogan peut de plus belle entretenir la rébellion syrienne, lâcher des milliers de migrants chaque jour sur l’Europe et obtenir de la décevante Mme Merkel des signes favorables à l’adhésion de la Turquie à l’Union Européenne.